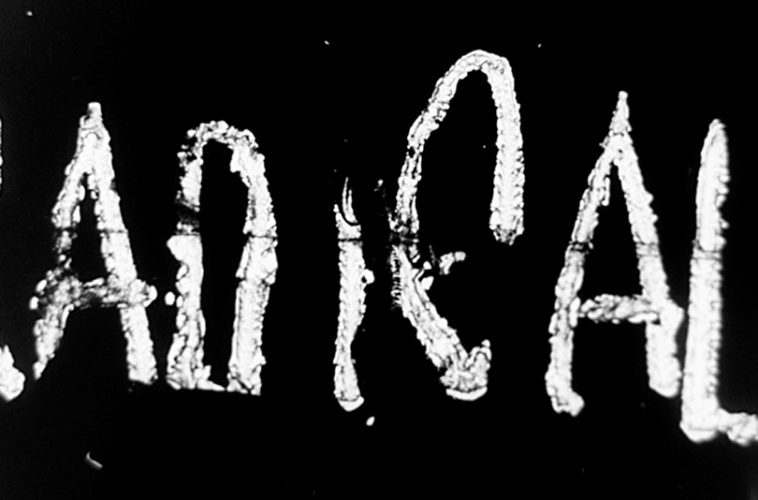

A Rebel Visionary: NANCY CUNARD

Portrait of one of the most intriguing muses of the 20th century at Paris' Quai Branly

26 Apr 2014

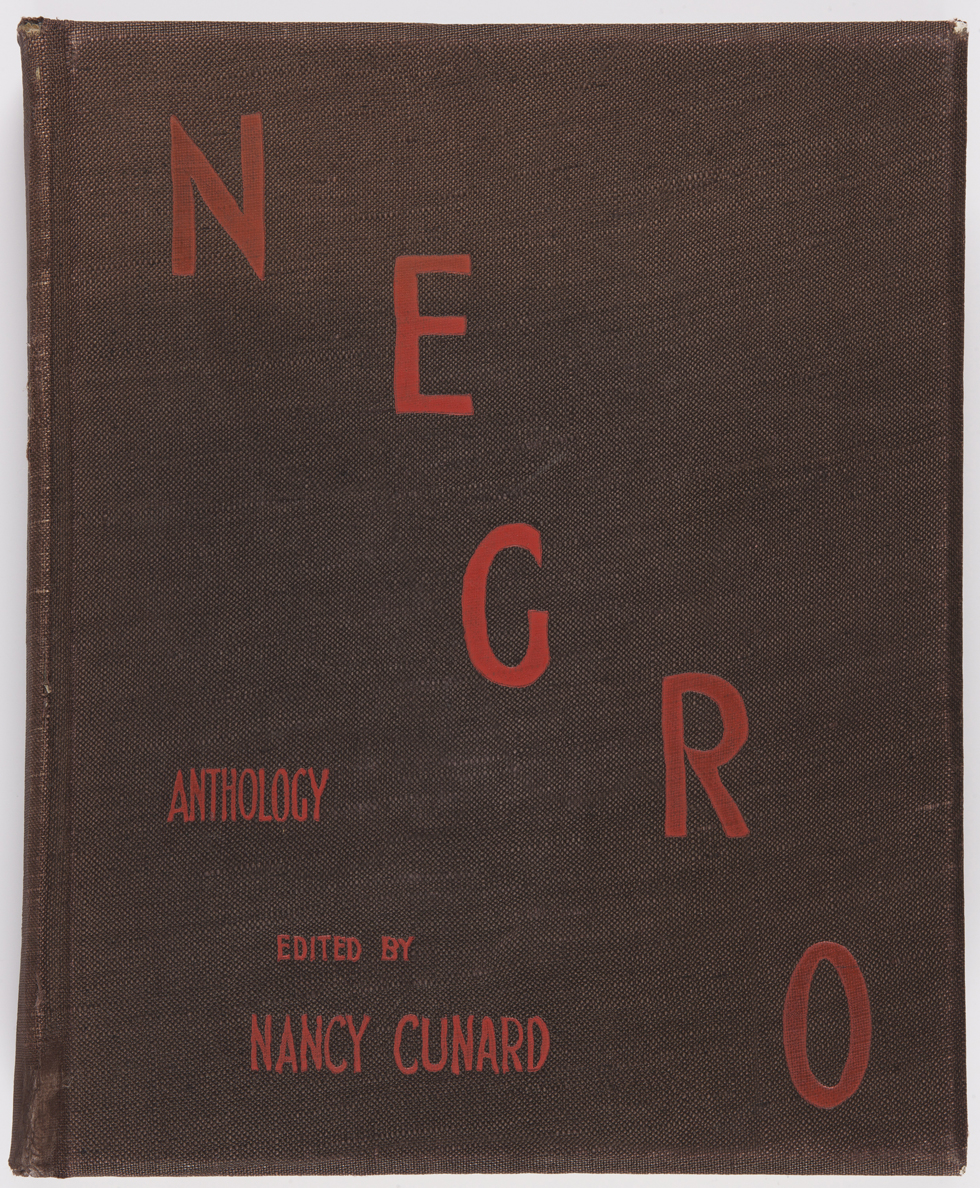

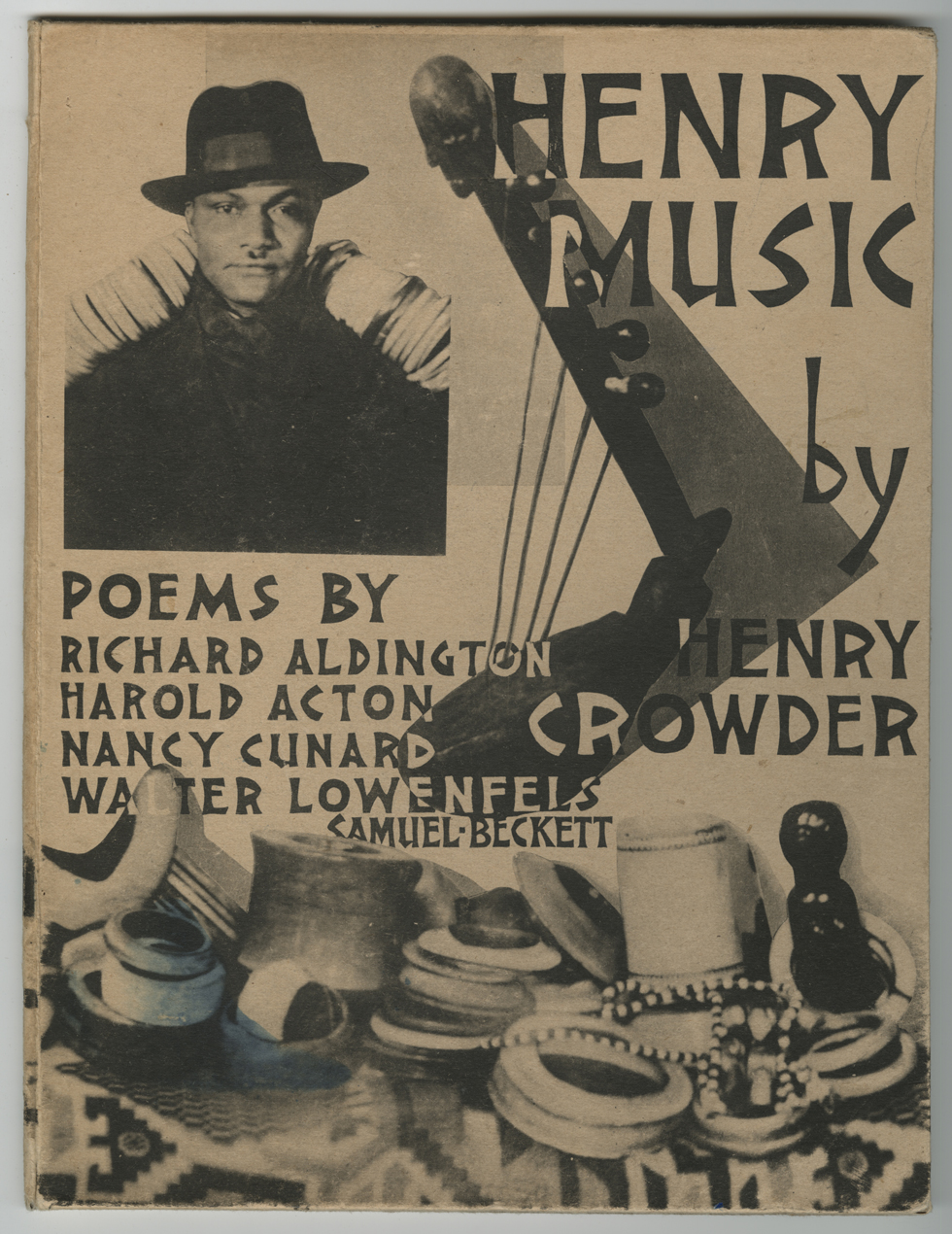

Defiantly unconventional, radical and provocative: Nancy Cunard is by far one of the most intriguing muses of the 20th century. All at once poet, political activist, publisher, muse, heiress and writer, Cunard incarnated the rebellious quintessence of the early 20th century avant-garde. Powered with the “belief in the sacred mission of art to change history” as Cunard said herself, the years following World War I gave birth to highly politically engaged literatary and artistic movements, envisioned as weapons to revolutionise society. Counting the likes of André Breton, Pablo Neruda and T.S. Eliot as her admirers, Cunard’s political activism came into full force when she published her seminal work Negro Anthology in 1934.

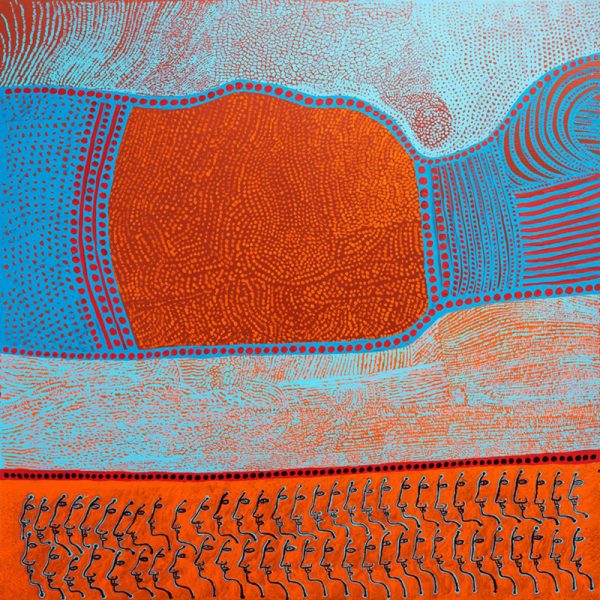

80 years on, this incredible book is now being celebrated in an exhibition entitled “Black Atlantic” at Paris’ quai Branly museum. Negro Anthology is something of a monument to black culture and history. Acting as both a history of the Black Americas and of Africa through time, Negro Anthology also chronicles the political and cultural history of its time.

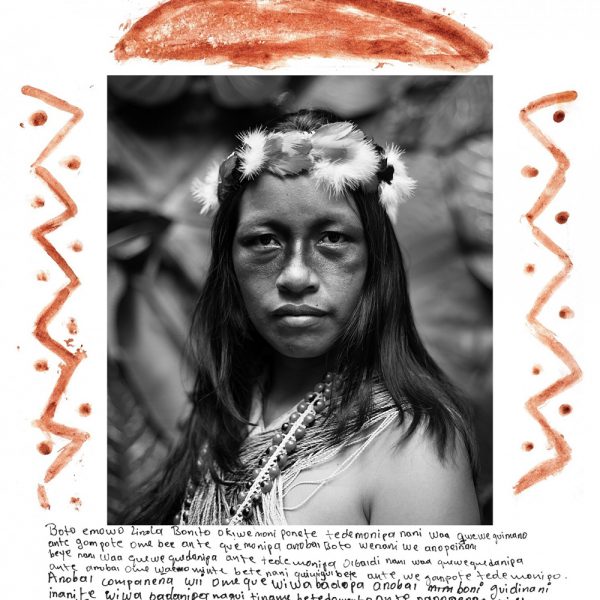

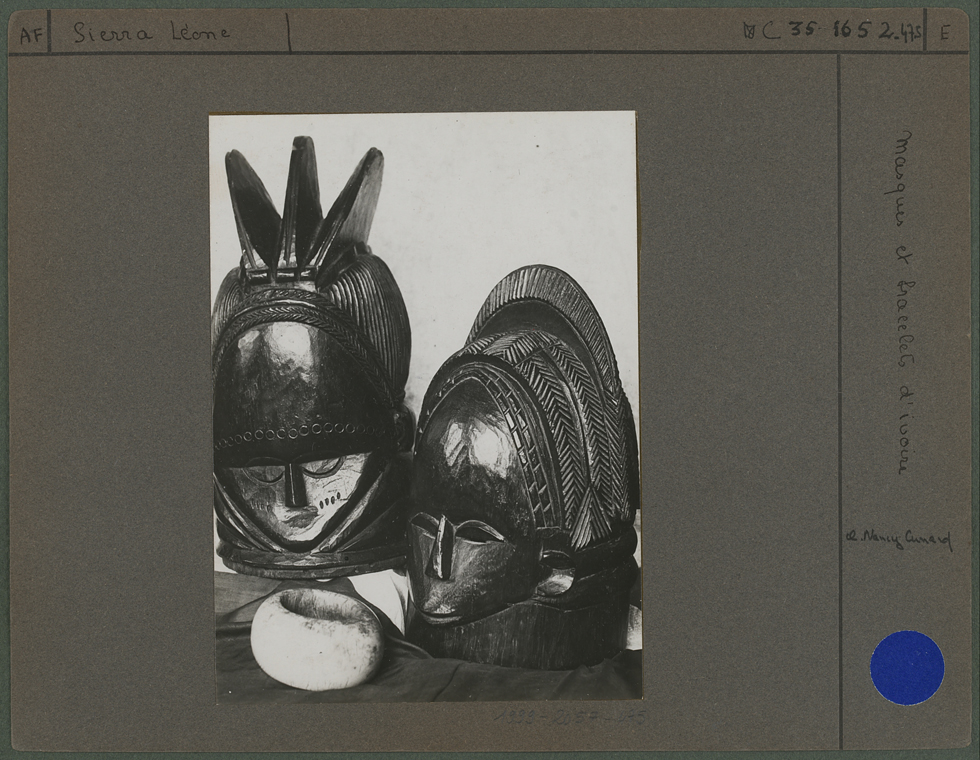

Across 858 pages, Negro Anthology fuses together Cunard’s interests in art, politics, history, art history, sociology, and popular culture, creating a major documentary enquiry. Featuring contributors from all around the world, Negro Anthology is a testament to the extensive networks Cunard built between 1910 and 1930. Negro Anthology features photographs, illustrations, poetry, fiction, documents as well as personal testimonies by 150 contributors: African-Americans, people from the Carribean, Africa, Latino-America, America and Europe, artists, journalists, militants and professors, including the likes of Theodore Dreiser, Zora Neale Hurston, W. E. B. Du Bois and Langston Hughes.

“a call to condemn racial discrimination and appreciate the accomplishments of a long-suffering people”.

A fervent supporter for the struggles of the disenfranchised, Cunard described the Negro Anthology as a call to “condemn racial discrimination and appreciate the … accomplishments of a long-suffering people”. The anthology aimed to provide an authentic portrait of black history and culture, rife with experiences of discrimination, colonialisation and segregation. Highly original in its composition and content, Negro Anthology revealed “the transnational and multi-faceted character of the anti-racist and anti-colonialist struggles of the 1930s” as curator Sarah Frioux-Salgas writes, illustrating the “international and transcultural formation that Paul Gilroy called “the Black Atlantic”.

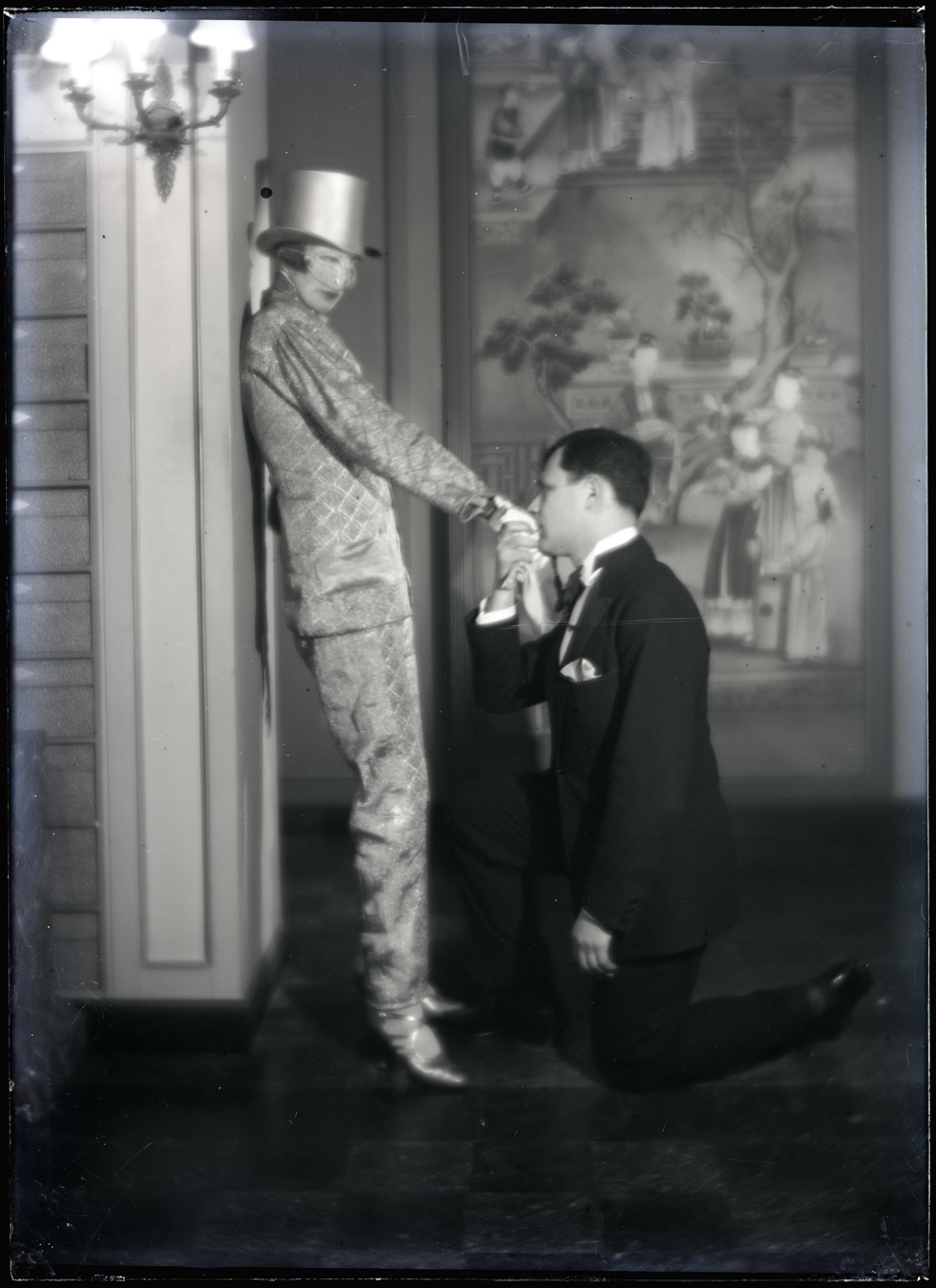

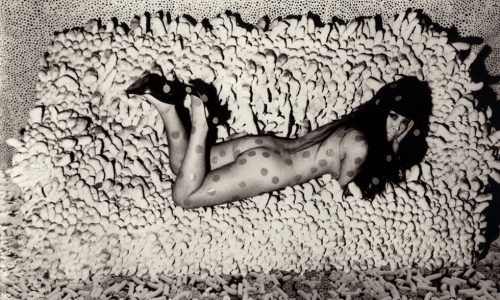

Moving from London to Paris in 1920, Cunard became involved with the literary Modernist, Surrealist and Dada movements. It was “a period of overt defiance of parental and social demands” and “artistic and sexual experimentation”, as she describes. Her lovers included the likes of Aldous Huxley, Tristan Tzara, Wyndham Lewis and Ezra Pound.

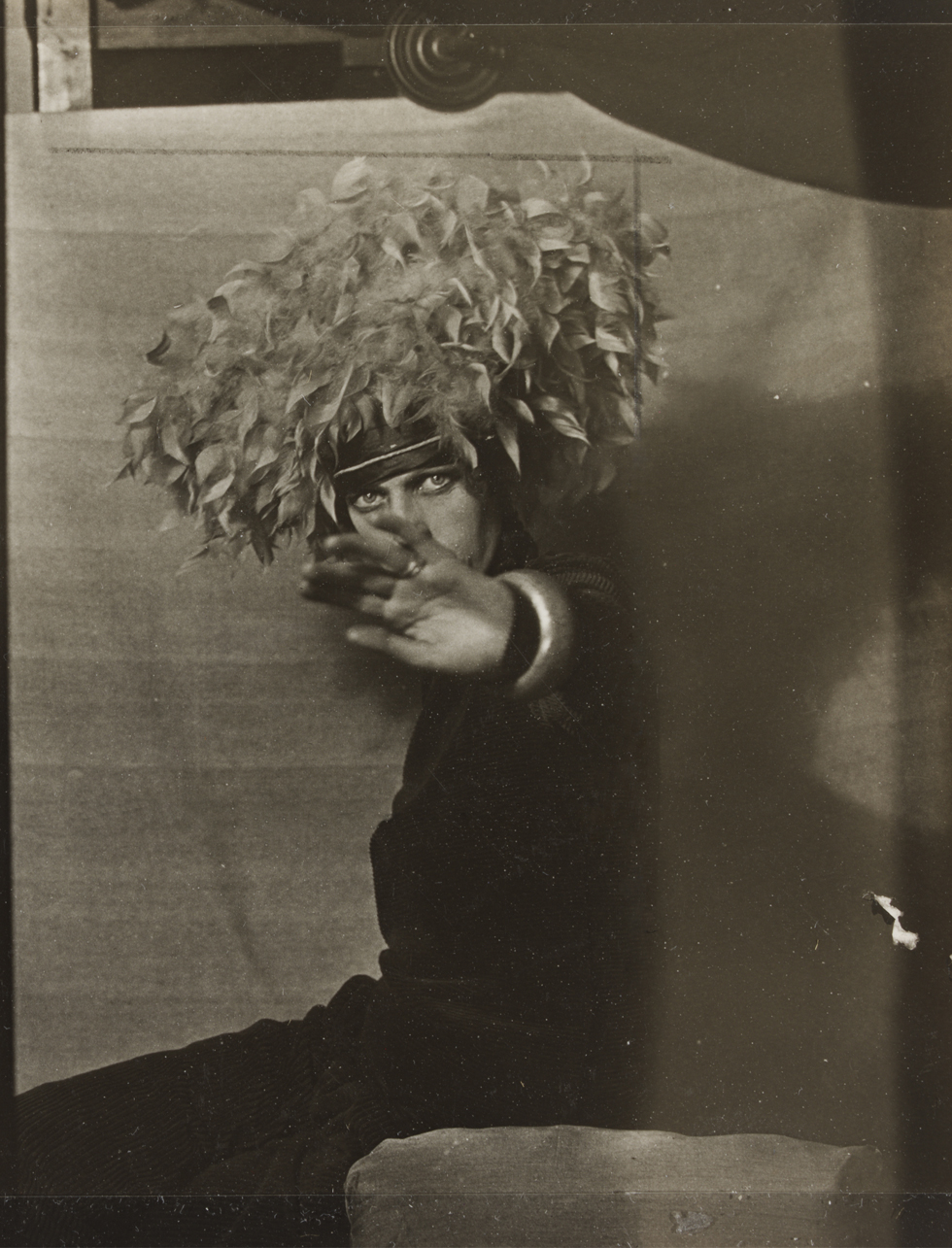

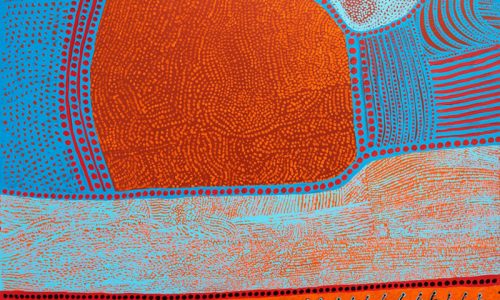

Immortalised in Surrealist artist Man Ray’s iconic portrait where she wears dozens of African bracelets made from from wood, bone and ivory, Cunard loudly displays her devotion to African arts. In a time when African culture was popularly identified with so-called “primitive” culture, Cunard’s choice was considered shocking and highly controversial, and it was dubbed by the high fashion vanguard as “the barbaric look”. As if echoing her publishing work of Negro Anthology, Cunard’s fierce sense of style becomes militant itself.

“All that remains is a furious sense of indignation”.

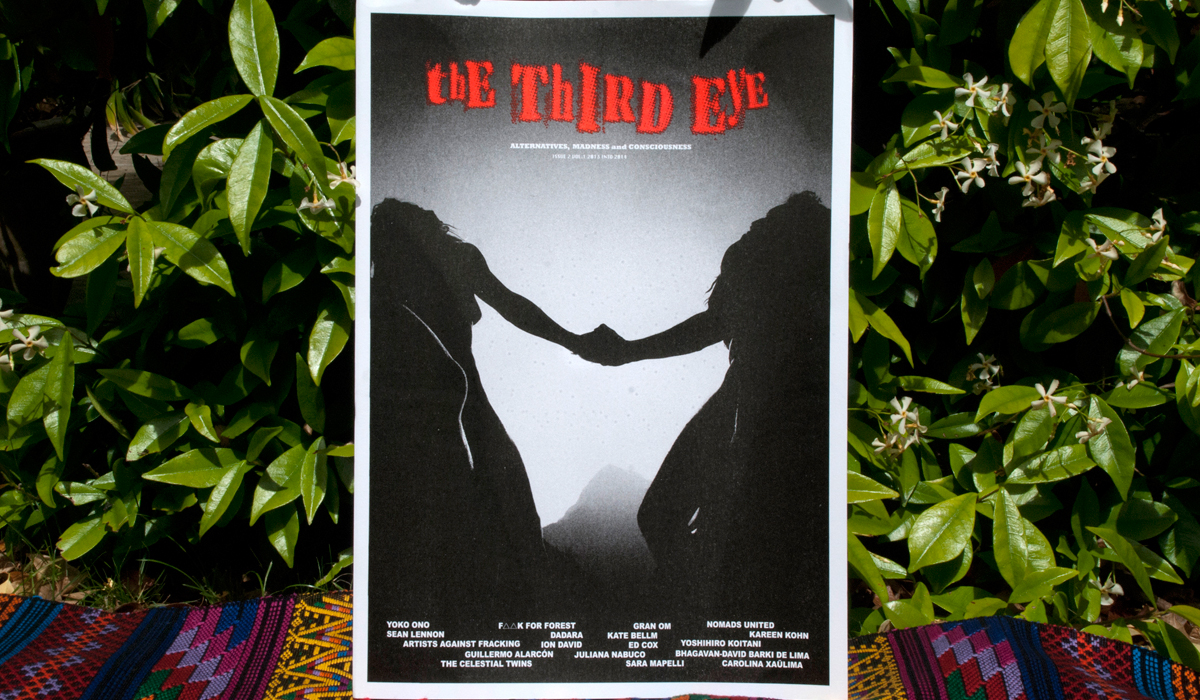

Cunard dedicated her life to fighting against racism and fascism. “All that remains is a furious sense of indignation”, wrote Cunard. Although Cunard lost herself to a spiral of self-destruction, her life’s commitment to justice continues to inspire us today. To Cunard, art, journalism, literature and publishing were militant forces of change. Here at The Third Eye, we also share this conviction.

Black Atlantic by Nancy Cunard is on view through May 18 at the Musée du quai Branly, Paris.

Photographs Courtesy of the Quai Branly museum

Text by Sophie Pinchetti